(A one hour mix made for Funboys Soundcloud)

The creator of the Devilfish, Robin Whittle, once defined techno music as the sound of “machines cranking over, lovingly tended”.

Well, it turns out that humans have been “tending” music machines, while they crank over, for a surprisingly long time!

The earliest known mechanical musical instruments date back to 9th-century Baghdad. These were apparently water-powered organs. A long time after that came clockwork-powered devices for playing bells or chimes. These were the basis of the popular music box, which eventually, by the mid-1700s, could be fitted inside a wrist watch or jewellery case. A hundred years later, the most popular musical instrument in the world, the piano, was the subject of efforts to automate it’s playing, resulting in the Pianola. Known generically as a “player piano”, these became the 20th century’s most popular and well-known music reproducers… until the arrival of the gramophone.

By the 1950s, Raymond Scott is inventing the polyphonic sequencer, drum machine and bassline generator, and working with Bob Moog. Only about 40 years after that, and look! we’ve got “techno”… I guess it’s no surprise that it has still got a bit of growing up to do!

So this mix, this story, is about the machines, and those who tended them, that helped get us to this point in the evolution of music.

Introducing the machine-tenders:

- Raymond Scott

- The BBC Radiophonic Workshop

- Laurie Spiegel

- Jean Michel Jarre

- Einzelgänger (Giorgio Moroder)

- Tangerine Dream

- Eno Moebius and Roedelius

- Kraftwerk

- Yellow Magic Orchestra

- Ryuichi Sakamoto

- Charanjit Singh

- CTI

- D.A.F.

- Severed Heads

and introducing the machines:

- the music box

- the rhythm modulator (Manhattan Research Inc.)

- the bassline generator (Manhattan Research Inc.)

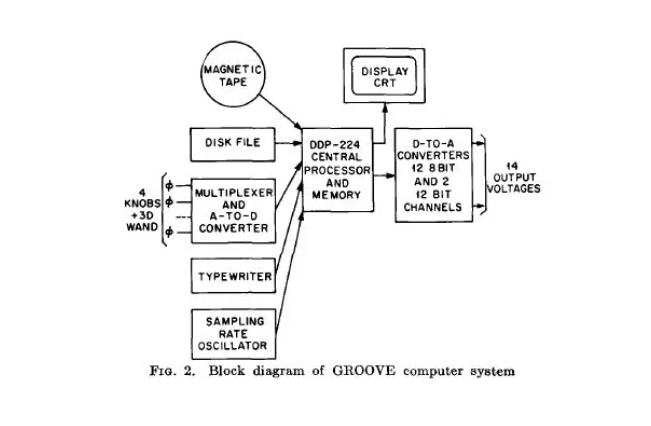

- The GROOVE system (Generated Realtime Operations On Voltage-controlled Equipment)

- EMS Synthi AKS

- Moog 960 sequential controller

- Korg SQ-10 analogue sequencer

- Roland MC-8 micro-composer

- Roland TB-303/MC-202/SH-101 synth/sequencer combos

Laurie Spiegel

As a music student and fledgling composer in New York at the end of the 60s, Spiegel fell in love with synths at first sight, or rather, first sound. Upon hearing a Buchla modular synth “Music went from black-and-white to color.” But what was really liberating for an unknown composer, Spiegel explains, is that “you were making the sounds yourself, as opposed to writing them down on a score and then hoping you could persuade a conductor and an orchestra to turn them into sound. You could immediately hear the realization of your ideas.”

By the mid-70s, she was working at Bell Labs, and had access to their unique music computer. “GROOVE stood for ‘Generated Realtime Operations On Voltage-controlled Equipment’,” says Spiegel. “Up until that point, people would put in their instructions and the program would run over night and they’d come back the next day and get 30 seconds of material. That was as bad as writing your music with paper and pencil as far as I was concerned. I was an improviser, I liked to make up stuff in direct contact with the sounds. Because it offloaded the actual generation of sound to the synths, GROOVE was freed up to be a control mechanism. You could program– visibly write what we called ‘transfer functions’– and you could hear the results straight away. And because the system was digital, you could store it all on magnetic tape, which meant you could pick up right where you left off the next day.”

In her words, “I automate whatever can be automated to be freer to focus on those aspects of music that can’t be automated. The challenge is to figure out which is which.”

from the Simon Reynolds article:

https://pitchfork.com/features/article/9002-laurie-spiegel/

Giorgio Moroder

Moroder needs no introduction, but what is rarely mentioned of his early work was that done under the alias ‘Einzelgänger’. In 1975 he produced a long-playing masterpiece of electronica of that same name, using simple sequencers, drum machines and synthesizers. It quickly disappeared from view. Then, only two years later, in the space of under 4 minutes, “I Feel Love” mapped out the future of modern dance music!

https://www.giorgiomoroder.com/music/einzelganger/

Charanjit Singh

Singh was a session musician in Bollywood, and played weddings to pay the bills. He spent the early 1980s experimenting with Indian raga on his newly acquired Roland TB 303 Bassline, TR 808 Rhythm Composer, and Jupiter 8 synthesizer. Then in 1982 he released his long-playing record album “Synthesizing: 10 Ragas to a Disco Beat” – one of the first anywhere to heavily feature the 303 in it’s intended role as a computer-controlled bass player. A commercial failure, the record regained attention as an acid house prototype in the early 2000s thanks to record collector Edo Bouman, who reissued the LP in 2010 on his label Bombay Connection. Singh told Bouman “Frankly, this was the best thing I did. Other albums are all film songs I just played. But this was my own composition. Do something all of your own, and you can make something truly different.'”

Tom Ellard (Severed Heads), on the TB-303 and related technology

“On ‘Clean’ I was using a CSQ-100 with my SH-1. It would hold 100 notes until you turned it off, so when I heard that Roland was bringing out a box that would keep the data it was very exciting to think about pre-programming live shows. No more tapping in the notes before each song. And it used batteries!

I bought a TB-303 just for that reason, I didn’t think about it being a bass instrument but good that it made a noise at all. As soon as it was released, I went sailing over to the local guitar shop in Sydney and paid what was a fairly meaty price for one of the first shipment. I recall that being late in 1982. Roland stuff was pretty quick to arrive in Sydney – they had a local branch and all. Didn’t inspect it at the shop, I just brought it home and started to figure it out.

I think on the second day I realised that it wasn’t that I was stupid, it was just the most unfortunate interface to create music ever conceived. For people who can now afford multiple sequencers and have a choice of working method, sure it’s cute, but if this was all you could afford for months you were sorely tempted to murder whoever devised this heinous thing. And the noise it made ranged from elephant fart to mock tuba.

Just like everybody else would end up doing I soon started tapping in mad combinations of notes to make burbles and squawks – some of which I recorded on cassette and can be heard on Eighties Cheesecake. That was fun for a little while, but I was pretty heartbroken. If only I’d kept at it, I could have claimed to have invented acid house! But instead I mostly went back to the CSQ-100 and waited for the MC-202 Microcomposer to arrive – which made up for everything by being utterly fantastic.

I just used the MC-202 for everything. The 303 sat around the studio for a while until I pointedly gave it to Robert Racic for free. Probably got sold for enormous profit, more fool me.”

Chris Carter (Throbbing Gristle, Chris and Cosey, CTI) on the Roland MC-8

“Understandably the MC8 didn’t excel at playing (or recording) fancy stuff like keyboard solos and lead lines, but what it did do exceptionally well was tight, multitrack sequencing, bass lines and rhythm patterns, frequently all at once. With the benefit of 8 separate CV/gate channels very complex polyrhythmic sequences can be produced with comparative ease and can also manage complex chords without a problem (assuming your synth is multi-voiced) by assigning multiple CVs to one channel. One of it’s undoubted features, like a lot of Roland sequencers and drum machines, is its rock solid timing. In full flow with all 14 channels outputting signals it always manages to steam along without taking a breath.”

“For classic examples of outstanding MC8 programming just listen to early 1980s albums by electronic bands such as Kraftwerk (The Man Machine), Human League (Dare), Landscape (From the Tea Rooms of Mars). Other notable users of the time were, myself and Cosey, Tangerine Dream, producer Martin Rushent (Altered Images, Pete Shelley, Human League), Hans Zimmer, Toto, Tomita and Suzanne Ciani, the latter pair employing assistants to enter note numbers for them. A number of artists used multiple MicroComposer set-ups. Tomita used at least two, one being the first model off the production line and an MC4. Toto used three, each one extensively modified by the original designer Ralf Dyck. Hans Zimmer used three, one for each of his various Moog and Roland modular systems, while Martin Rushent used an MC8 and an MC4.”

http://www.chriscarter.co.uk/content/sos/roland_mc8.html

MIX CREDITS

- Personal recording of a music box playing English folk song “D’ye ken John Peel?” manu. circa 1900

- The Rhythm Modulator – followed by

- The Bassline Generator – both inventions by Raymond Scott, recordings perhaps 1950s?

- “Brio” – The BBC Radiophonic Workshop, early 70s

- “Drums” – followed by

- “Patchwork” – both by Laurie Spiegel, produced using the GROOVE computer at Bell Labs, mid to late 70s

- “Oxygene” (excerpt from the middle of side 2) – Jean Michel Jarre, 1976

- “Untergang (Ruin)” – Einzelganger, 1975

- “Basslich” – Einzelganger, 1975

- “Phaedra” (excerpt from the middle of the record) – Tangerine Dream, 1973

- “Base And Apex” – Eno Moebius and Roedelius, 1978

- “Spacelab” – Kraftwerk, 1977

- “Einzelganger (reprise)” – Einzelganger, 1975

- “La Femme Chinese” – Yellow Magic Orchestra, 1978

- “Riot In Lagos” – Ryuichi Sakamoto, 1980

- “Raga: Bhairavi” – Charanjit Singh, 1983

- “Dancing Ghosts” – CTI, 1984

- “Der Mussolini” – Deutsche Amerikanische Freundschaft, 1981

- “We Have Come To Bless This House” – Severed Heads, 1984